“From the square up above, you could see other hills, azure almost. I leaned against the church in the sun. In that warmth and silence, I felt an inkling of hope. What was happening seemed impossible to me. Life would go on one day, safe and sound, like now. I had forgotten this for too long. The blood and raids could not go on forever.”

| IL FUGGIASCO Cesare Pavese Sui fienili e nelle stalle da un pezzo non volevano piú nessuno, perché poi succedeva che venivano gli altri a far rappresaglia. Davano un piatto di minestra e del pane solo a chiederlo, ma dicevano di andarselo a mangiare lontano; ci voleva un discorso ben grosso per trattenerli sulla porta. Ogni tanto pioveva e bisognava ripararsi sotto i ponti. Quando trovai quella cappella abbandonata non dissi niente a nessuno e, ficcata della foglia nel sacco, mi ci misi a dormire. Di scappare e ascoltare ne avevo abbastanza. Mi svegliai ch’era ancor notte piú che giorno e dalla finestretta non entrava tanta luce da vederla. S’era rimesso a piovere forte, e qualche spruzzo m’arrivava in faccia. Stavo disteso dentro il sacco e mi godevo il tepore. Non lontano, un cane abbaiava e lo immaginavo randagio sotto l’acqua e dolorante di fame. In quel buio invernale sembrava la voce di tutta la terra. Nel dormiveglia sussultavo. La pioggia all’alba si schiarí e mi vidi intorno delle vigne vendemmiate. Tutto era fango e foglie rosse. Della cappella restava ancora un vetro rosa screpolato e da quel vetro si vedeva la campagna. Nella buona stagione dovevano starci per guardia dell’uva. Qualunque cosa succedesse, era un posto fuorimano. Passai la giornata in paese. Era domenica e giocavano alle bocce. Io me ne stetti contro il muro a guardare le facce e conoscerli; li ascoltavo scherzare e gridare. Di lassú s’intravedeva nella nebbia tutta la vallata e la strada grande e le colline in faccia che calavano a Po. Un paese di quella valle era stato bruciato, e della gente uccisa. I piú dicevano per dire, ma un piccolotto che ascoltava disse subito: – Per passare è meglio di là; dove han bruciato non c’è piú sorveglianza. Col buio tornai nella cappella e, inquieto com’ero, avrei voluto che piovesse. S’era invece levato un gran vento che sbatteva le stelle e rifaceva quella notte ch’ero uscito sulle colline. Nel vento tutto era nitido e nero e si sentivano le foglie rotolare. Dormii appena. Il vento durò qualche giorno. C’era di buono che asciugava la campagna. Non sapevo risolvermi a lasciare il paese. Quell’ultima barriera di colline mi faceva paura. Mi ritrovai col piccolotto delle bocce. Parlava poco ma capiva al volo. Mi aveva condotto nel suo cortile, dietro casa, e qui d’accordo con le donne portato un piatto di minestra. Poi a queste avevo dovuto raccontare delle storie, perché volevano sapere quando la guerra finiva. – Durasse anche un secolo, – dicevo, – chi sta meglio di voi? – C’era ancora sotto il portico la chiazza di sangue dove avevano ucciso il maiale. – Vedete com’è, – disse il mio giovanotto, – questa fine la dobbiamo far tutti. Piú tardi, in cortile, gli avevo chiesto se non si vergognava di parlare soltanto. Lui mi aveva guardato ridendo e fatto un cenno alla casa e alla finestra illuminata. — Avevo anch’io una casa, – gli dissi. A lui lasciai vedere dove dormivo la notte. Mi accompagnò ch’era già buio e mi disse che, se bastasse dormire in chiesa per stare al sicuro, le chiese sarebbero piene. – Qui non è piú una chiesa, – dissi, – sull’altare ci han pestato le noci e acceso il fuoco per terra. — Ci venivamo da ragazzi a giocare, – mi disse. Poi mi disse com’era in paese e che tutti vivevano nella paura che sullo stradale toccasse una fucilata a un soldato o fermassero un camion. – A O… hanno incendiato anche la chiesa, – dissi. — Bruciassero queste soltanto, – disse lui, – sarebbe una cosa. Ma di tutte le chiese che avevo veduto, la mia cappelletta era la piú sicura. Raccogliemmo tutti i rami che trovammo, e coi cartocci della meliga buttati accendemmo un po’ di fuoco nel cantuccio sotto la finestra. Poi seduti davanti alla fiamma fumammo nella pipa, come fanno i ragazzi. Dicevamo scherzando: – Per dar fuoco, sappiamo anche noi –. In principio non ero tranquillo, e uscii fuori a studiare la finestra, ma il riflesso era poco e, di piú, parato da un rialto. – Non si vede, no, no, – disse Otino. Allora parlammo un’altra volta delle facce del paese e di quelli che avevano paura piú di noi. – Anche loro non vivono piú. Non è vivere. Lo sanno che verrà il momento. — Siamo tutti in trincea. Otino rideva. Lontano scoppiò una fucilata. — Incominciano, – dissi. Tendemmo l’orecchio. Ora il vento taceva e i cani abbaiavano. – Andate a casa, – dissi. Spensi subito il fuoco. Passai la notte nel puzzo di fumo, tremando ai pensieri. Mi pareva, rivoltandomi nel sacco, che il suo scroscio riempisse la notte. L’indomani studiai risoluto la barriera di colline che mi attendeva. Erano brune e disseccate dal vento e dalla stagione, limpide sotto il cielo. Il pericolo non era lassú, ma di là, sulle strade d’accesso ai ponti e alla piana. Nessuno sapeva dirmi la libertà di quelle strade. I nostri che battevano i boschi avevan certo provocato una cintura di terrore agli sbocchi. Era prudente abbandonare la cappella per cacciarsi laggiú? Salii la stradicciuola a comprare del pane in paese. La gente mi guardava dagli usci, sospettosa e curiosa. A qualcuno facevo un cenno di saluto. Dalla piazza in alto, si vedevano altre colline quasi azzurre. Mi fermai contro la chiesa, sotto il sole. Nel tepore e nel silenzio ebbi un’idea di speranza. Mi parve impossibile tutto quel che accadeva. La vita avrebbe un giorno ripreso, sicura e ferma com’era in quest’attimo. Da troppo tempo l’avevo dimenticato. Il sangue e il saccheggio non potevano durare per sempre. Stetti un pezzo con le spalle alla chiesa. Ne uscí una ragazza. Si guardò intorno e discese la strada. Per un istante entrò anche lei nella speranza. Scendeva guardinga sui ciottoli scabri. Ma fece la donna e non si volse a guardarmi. Sulla piazzetta non vedevo anima viva e i tetti bruni ammonticchiati, che fino a ieri m’eran parsi un nascondiglio sicuro, adesso mi parvero tane da cui si fa uscire la preda col fuoco. Il problema era soltanto resistere alla fiamma finché un giorno fosse spenta. Bisognava resistere, per ritrovare un giorno la speranza intatta. La sera vennero voci di un’azione nella vallata accanto, contro un paese che non aveva mai avuto un solo guaio. Cosí giuravano. Difatti non s’era sentita nemmeno una fucilata: le stalle erano state saccheggiate e dei fienili incendiati. La gente, fuggita nei boschi, sentiva i suoi vitelli muggire e non poteva accorrere. Era stato sul tardo mattino, proprio nell’ora ch’io guardavo dalla chiesa. Andai a cercare Otino nel campo. Fermò uno dei buoi per la coda, e mi disse: – Stanno freschi. Sono giornate che passano presto. Viene il maltempo e chi è piú capace a lavorare. Gli dissi che poteva toccare anche a lui. — Ma è per questo, – mi disse, – che diamo dentro a finire. Poi si sta chiusi fino a marzo. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Non ero stato il solo quel giorno a osservare le montagne che parevano nuvole. La padrona di Otino era uscita fra i pini e s’era fermata un momento a guardarle. Poi rientrando aveva appeso il secchio d’acqua in cucina e messo il latte al fuoco per il piccolo Guido. Da un pezzo era passato Otino coi buoi ma Guido dormiva e non era salito sul carro. La donna s’era fatta alla finestra e aveva chiesto a Otino se ero sempre in paese. — Dorme sempre a San Grato? e chi è? – Allora Otino aveva detto che con me si poteva parlare ma che chiedere a uno «chi sei?» non si può. – Dalla montagna? forse viene di lassú? – gli aveva detto la padrona. — Gli scarponi li ha, – disse Otino. Nel pomeriggio erano andati con le sorelle di Otino a raccogliere le ultime mele. Guido corse avanti col cesto, e un grosso nugolo di storni s’era levato dai filari. Fecero un rombo come fosse un motore. Guido si chinò e ai fuggiaschi tirò una manciata di sassi, strepitando a mitragliatrice: – Tatatà, tatatà. — Fatti furbo, – gli disse la donna, – sei vecchio quest’anno. Le ragazze ridevano. – Siete vecchie voialtre, – disse Guido. – E vi piace ballare. Volete che la guerra finisca per tornare a ballare. — Tu non vuoi che finisca? – disse una. — Non può finire, – disse Guido, – quando la guerra è dappertutto come adesso, non può finire mai piú. La padrona disse: – Raccogliamo queste mele. Dalla vigna Guido aveva fatto una corsa al campo di Otino e rotolando in mezzo ai solchi chiamò se c’ero anch’io. — Chi? – gridò Otino. — Quell’uomo che dorme a San Grato. San Grato! — È andato via. Via! – rispose Otino, senza fermare l’aratro. — Dovevi dirgli di venire a casa nostra. — Perché? – gridò Otino, ridendo. — Perché le donne sono vecchie. Vecchie! Poi Guido corse fino ai piedi della costa, scese ancora, arrivò tanto in basso nel campo, che invece di vedere le colline a strapiombo le travedeva lontane, fra gli steli del canneto. Qui si nascose nelle canne, e pensò che cominciasse un’azione, e si tastava le mele nella camicia, indeciso se farne pallottole o pane. Poi le morse e scagliava i torsoli agli uccelli. Cercò piú volte col tiro di passar sopra alla cappella di San Grato, per non farsi un nemico di chi ci dormiva, e s’accostò alla cappella strisciando per terra. A quell’ora io scendevo dalla collina del bosco, dove salivo per dominare la valle. Lassú era pieno di nascondigli e di valloni, di stradette perdute nella macchia, di salti improvvisi nel vuoto. Avevo visto di lassú nel campo bruno i buoi d’Otino che sembravano fermi. Nell’aria fresca si sentivano le voci suonare tranquille, e se un urlo, uno sparo, avesse rotto quella calma i buoi laggiú non si sarebbero mossi. Quella sera ero contento; dovevo mangiare una minestra nel cortile di Otino, poi tornarmene solo nella vecchia cappella e star nascosto. Pensavo che, se nessun armato sarebbe mai salito per quelle strade, il mio rifugio era come un gioco, come un’insolita villeggiatura di convento. In alto, sulla collina, avevo ritrovato quella speranza, quella libertà, e capivo che per viverla bastava pensarla reale. Qui non c’erano le case, le soffitte e le piazze dove il pericolo guatava all’angolo. Qui nessuno mi aspettava a un appuntamento mortale. Qui non c’era che terra e colline e bastava appiattirsi alla terra per vivere ancora. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Fine. | THE FUGITIVE Cesare Pavese They hadn’t wanted anyone in their haylofts and sheds for some time now, because others would inevitably come and retaliate. They’d provide a bowl of soup and some bread only if asked, but said it had to be eaten somewhere far; it took some pretty convincing words to keep them at the door. Every now and then, it would rain and you needed to find shelter under bridges. When I found that abandoned chapel, I didn’t say anything to anyone and, after putting leaves in my sack, I slept there. I had had enough of running and listening. I woke up when night had not fully turned to day and hardly any light could be seen through the tiny window. It had started to rain heavily again, and sprinkles wet my face. I was lying inside the sack and enjoying the warmth. Not far away, a dog was barking, and I imagined it was a stray, soaked by the rain and suffering from hunger. In that winter darkness, it sounded like the voice of the entire earth. I shuddered as I dozed. At dawn the rain lifted and I saw all around me harvested vineyards. Everything was mud and red leaves. Of the chapel, a peeling pinkish pane remained, and from that pane I could see the countryside. In good weather, they probably guarded the grapes from there. Whatever happened, the place was off the beaten track. I spent the day in town. It was Sunday, and they were playing bocce. I leaned against the wall looking at faces and getting to know them: I heard them joke and shout. From up there, you could see the whole valley under the fog, and the main road, and the hills opposite, which dipped towards the Po. One town in that valley had been burned to the ground and people killed. Most said it just to say something, but a young guy who was listening in quickly added, “That’s the best way through; no one’s guarding the burned down town anymore.” When it was dark, I returned to the chapel, and I was so restless I wished it were raining. Instead, the wind had picked up, and it was so strong it beat the stars and recreated the night I’d come out onto the hills. The wind made everything vivid and black and you could hear the leaves rolling. I barely slept. The wind lasted a few days. The good thing was that it dried the countryside. I couldn’t make up my mind to leave the town. That last wall of hills scared me. I met up with the young guy from the bocce again. He didn’t talk much but caught on quickly. He led me to his courtyard, behind the house, and here, in accord with the women brought me a bowl of soup. Then I had to tell these women stories because they wanted to know when the war was going to end. “Even if it were to last a century,” I said, “who’s better off than you are?” There was still a puddle of blood under the portico where they’d slaughtered the pig. “See how it is,” said my young man, “it’s how we’ll all end up.” Later, in the courtyard, I asked him if he wasn’t ashamed to be all talk and no action. He looked at me, laughing, and motioned to the house and the lit window. “I had a house too,” I said. I let him see where I slept at night. He accompanied me there after dark and said that if it all it took was a church to stay safe, the churches would be full. “This isn’t a church anymore,” I said. “They’ve cracked nuts on the altar and lit a fire on the floor.” “As kids, we used to come here to play,” he said. Then he told me what it was like in the town and that everyone was afraid a soldier would get shot or a truck stopped on the road. “In O…they burned down even the church,” I said. “If that’s all they burned,” he said, “it’d be one thing.” But of all the churches I had seen, my little chapel was the safest. We gathered all the branches we could find, and with the abandoned corn husks we lit a small fire in the niche under the window. Then we sat in front of the fire and smoked like kids. We’d say jokingly, “We’re good at lighting fires too.” I was worried at first, and I went outside to examine the window, but there was very little light reflected and, what’s more, it was hidden by the ledge. “You can’t see anything, no, no way,” said Otino. So we talked about the people of the town again and of those who were more afraid than we were. “They’re not living anymore either. This is not living. They know the time will come.” “We’re all in the trenches.” Otino was laughing. A gun shot sounded in the distance. “They’re starting,” I said. We listened carefully. Now the wind was silent and the dogs were barking. “Go home,” I said. I quickly put out the fire. I spent the night immersed in the stench of smoke. My thoughts made me tremble. As I tossed and turned in my sack, it was as if its rumbling filled the night. The next day I finally examined the block of hills awaiting me. They were brown and dried by the wind and the season, limpid under the sky. The danger was not up there but beyond, on the roads that accessed the bridges and the plains. No one could tell me if those roads were free. Our comrades, who combed the woods, had most certainly provoked a ring of terror at the openings. Was it wise to leave the chapel to go up there? I climbed the path to buy some bread in town. People stared at me from their doorways, suspicious, curious. To some, I waved hello. From the square up above, you could see other hills, azure almost. I leaned against the church in the sun. In that warmth and silence, I felt an inkling of hope. What was happening seemed impossible to me. Life would go on one day, safe and sound, like now. I had forgotten this for too long. The blood and raids could not go on forever. I stayed leaning on the church for a bit. A girl came out. She looked around her and descended the street. For a moment, she, too, became a part of that hope. She was going down the rough cobblestones carefully. But she pretended to be a woman and didn’t turn to look at me. Not a soul could be seen in the square and the assembly of brown rooftops, which until yesterday seemed a safe haven, now seemed like dens where prey could easily be flushed out with fire. The only thing to do was to resist the flame until one day it was put out. You had to resist in order to find your hope intact again one day. That evening brought rumours of an action in the nearby valley, against a town that had caused not even one disturbance. So they said. In fact, not one shot had been heard. The barns were ransacked and the haylofts burned. The people, who had taken cover in the woods, could hear their calves mooing and couldn’t run to help. It had happened in the late morning, right when I was watching from the church. I went to look for Otino in the field. He stopped one of his oxen by the tail and said “It’s a tough situation. These days pass quickly. The bad weather is on its way and who’ll be able to work then?” I told him it might happen to him too. “That’s why,” he said, “we’re trying to get this done. Then we’ll stay inside until March.” . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . He wasn’t the only person that day to observe the mountains that looked like clouds. Otino’s woman, too, had come out among the pines and stood looking at them. Then she went back in, hung a bucket of water in the kitchen and put milk on the stove for little Guido. Otino had passed with his oxen a while ago but Guido was sleeping and hadn’t climbed onto the cart. The woman leaned out the window and asked Otino if I was still in town. “Is he still sleeping in San Grato? Who is he?” So Ottino said I was someone you could talk to, but that asking “who are you” was out of the question. “From the mountains? Maybe he’s from up there?” the woman said. “He does have the boots,” Otino said. In the afternoon, they’d gone with Otino’s sisters to pick the last apples. Guido ran ahead of them with a basket, and a huge cloud of starlings lifted off the vines. They made the sound of a motor. Guido bent down and threw a handful of pebbles at the fugitives, making the sound of gunfire, “bang, bang, bang.” “Smarten up,” said the woman, “you’re old this year.” The girls were laughing. “You’re the old ones,” Guido said. “And you like to dance. You want the war to end so you can go dancing again.” “Don’t you want it to end?” one asked. “It can’t end,” said Guido, “when the war is all around us like now, it can never end, never again.” The Woman said, “Let’s pick these apples.” From the vineyard Guido had run to Otino’s field and, rolling down the furrows, he asked if I was there too. “Who?” asked Otino. “That man who’s sleeping in San Grato. San Grato!” “He left. Go away!” said Otino without stopping the plough. “You should’ve told him to come to our house.” “Why?” Otino shouted, laughing. “Because the women are old. Old!” Then Guido ran to the foot of the slope, went down some more, descending so low in the field that the hill, instead of looming, looked distant through the cane thicket. Here, he hid among the canes and imagined an action was about to take place, and he touched the apples in his shirt, unsure whether to make them bullets or bread. Then he bit them and threw the cores at the birds. He tried more than once to fling them past San Grato chapel so as not to make an enemy of the man who was sleeping there, and, he slithered to the chapel. At that hour, I was descending the hill in the woods where I went to look out over the valley. It was full of hiding places up there, and of deep vales, of roads lost in the bush, of precipitous cliffs over the abyss. From up there, I had seen Otino’s oxen in the brown field. They seemed motionless. I could hear calm voices ringing in the cool air, and if a cry, a shot had shattered that stillness, the oxen down below would not have moved. I was happy that evening; I was to eat soup in Otino’s courtyard, then return to the old chapel and stay hidden. I thought that, if no soldier were ever to make it up those roads, my shelter would be like a game, like some strange holiday in a convent. Up above on the hill, that hope, that freedom had been restored, and I realised that to live it, all I had to do was believe it was real. There were no houses here, no attics, no squares where danger lay waiting behind every corner. Here, no deadly appointment was waiting for me. Here there was nothing but land and hills and all you had to do was lie flat on the earth to live some more. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . The end. Translation ©Matilda Colarossi 2025 |

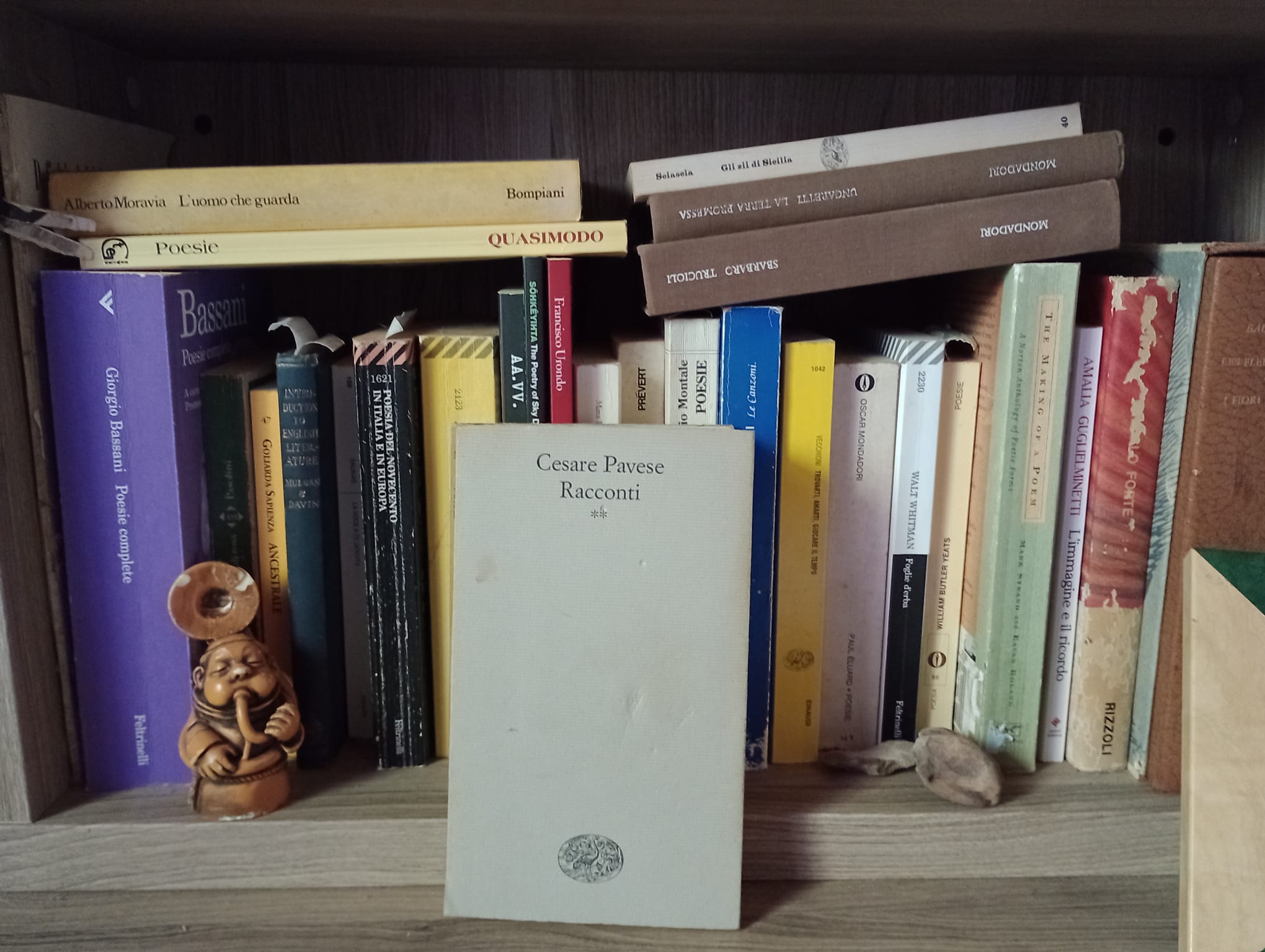

This short story by Cesare Pavese is from the book Racconti, Einaudi, Torino, 1968. pp 445-449. I found the book in an antique market, my usual book hunting-ground.

I’ve been working on this short story for many days. I leave it, go back, change things. Leave it. Go back. Change other things.

Stories of the different types of pain war can and does inevitably inflict intrigue me because they make me understand that, in fact, we must certainly despise peace if we continue waging war. Yes, despise, because if that weren’t the case, no president or premier or king could force the masses to take part in it.

They say there is strength in numbers; I say numbers unarmed, unprotected, unassisted are dead numbers. That’s what made the Italian partisans of WWII so amazing: single digits really, compared to the enormous number of fascist soldiers (both German and Italian); and they were able to change history, to make life better for us… For a while. Until we forgot. – M.C.

This work is licensed under https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ The fugitive by Cesare Pavese, paralleltexts.blog ©Matilda Colarossi 2025

Tip jar

Choose an amount

Thank you for helping to keep paralleltexts.blog publicity free. Your contribution is greatly appreciated.

Tip