“Cultivating Memory is still today a precious vaccine against indifference, and it helps to remember, in this world so full of injustice and suffering, that each and every one of us has a conscience and can use it.” -Liliana Segre

| LILIANA SEGRE: TEMO DI VIVERE ABBASTANZA PER VEDERE COSE CHE PENSAVO LA STORIA AVESSE DEFINITIVAMENTE BOCCIATO, INVECE ERANO SOLO SOPITE. | LILIANA SEGRE: I’M AFRAID I WILL LIVE LONG ENOUGH TO SEE THE THINGS I THOUGHT HISTORY HAD DEFINITELY QUASHED WERE, INSTEAD, ONLY DORMANT. |

| Estratti dal suo racconto: | Excerpts from her story: |

| Mi ricordo le tre fasi: la prima del pianto, che apparteneva a tutti, grandi, piccoli, uomini, anche giovanotti forzuti, tutti piangevano. Quando poi il treno passò il confine e ai ferrovieri italiani subentrarono quelli Austriaci e poi Tedeschi, e si vide il treno andare verso nord, allora veramente i pianti arrivarono… Da nessuna parte, perché nessuno ci ascoltava. Nessuno ci diede un bicchiere d’acqua alle stazioni. Quelle fotografie di repertorio in cui si vedono visi dolenti che si affacciano a grate di finestrini dei carri bestiame… ci rappresentano, fanno sì che non si possa più girare la faccia dall’altra parte: eravamo come i vitelli che vanno a morire. Chi si interessava di noi? Dopo se ne è parlato, quando già erano morti i vitelli… Dopo s’è tanto parlato di Shoah, ma al momento nessuno diede un bicchiere d’acqua. Alla prima fase del pianto subentrò una seconda fase rarefatta, kafkiana, importante: gli uomini religiosi, i pii, più fortunati, si riunivano nel centro del vagone e, dondolandosi, salmodiavano, lodando Dio anche in quel momento. Pregavano anche per noi, che non sapevamo pregare. Il vagone era buio, la gente appoggiata alle pareti del vagone e quegli uomini, al centro, si dondolavano pregando, con lo scialle di preghiera: era una visione straordinaria. La terza fase fu quella del silenzio: quando si è già detto tutto, quando non c’è più niente da dire, ma è il momento di massima comunicazione con l’altro. Non è solitudine quando si è con l’altro a cui vuoi bene e non dici una parola. Io e il mio papà non avevamo più niente da dire, in realtà avevamo parlato sempre pochissimo io e lui, perché non avevamo bisogno di tante parole. Ma il momento massimo è il momento di comunione, così profondo, così silenzioso. Allora l’ho capito: quando la vita è piena di rumore, di auricolari, di musica che sovrasta gli altri suoni, persino quelli delle casse al supermercato, non è mai un momento importante della nostra esistenza. Un momento importante della vita è sempre di silenzio assoluto, quando la coscienza e il cuore e la mente hanno la loro massima espressione. (Parte 3) | I remember three phases: the first was made of tears, which did not spare anyone, old, young, men, and even burly youngsters. Everyone cried. Afterwards, when the train crossed the border and the Italian railwaymen were replaced with Austrian and German ones, and we saw the train move north, then tears really came…Out of nowhere, because no one was listening. No one gave us a glass of water at the stations. Those stock photos in which you see stricken faces looking out from behind the bars of the windows in the boxcars…they are us, and they would make looking the other way impossible forevermore: we were like calves going to the slaughter. Who cared about us? They talked about it afterwards, when the calves were already dead…They talked and talked about the Shoah afterwards, but at the time, no one gave us a glass of water. The first phase made of tears was followed by a second rarefied one, Kafkaesque, important: religious men, pious men, more fortunate men, came together in the centre of the cars and, rocking, they chanted, praising God, even then. They prayed for us too. For we did not know how to pray. The boxcar was dark, people leaned against the walls, and those men stood in the centre. Rocking, they prayed wrapped in their prayer shawls: it was an extraordinary sight. The third phase was one made of silence: It is when everything has been said, when there is nothing left to say. But it is the moment of maximum communication. When you are with a person you love and are silent, that is not solitude. My father and I had nothing more to say. In truth we had always spoken very little, because we did not need many words. But the greatest moment is the moment of communion, a moment so profound, so silent. And I understood it then: when life is full of noise, of earplugs, of music that drowns out the other sounds, even those of the check-outs in the supermarket, it is never an important moment in our lives. An important moment in life is always a completely silent one, when our conscience and heart and mind express themselves to their fullest. (Part 3) |

| Lo porto con grande onore il mio numero, il 75190 di Auschwitz. In questo i nazisti sono riusciti perfettamente. Chi è tornato per raccontare, è rimasto essenzialmente il numero di Auschwitz. Volevano sostituire con un numero l’identità di milioni di uomini e donne e una volta morti, non sarebbero state più persone, ma numeri: il niente a raccontare di loro. E chi è tornato è rimasto essenzialmente quel numero. Io lo ripeto sempre ai miei figli: sulla mia tomba, se sarò una delle poche persone della mia famiglia ad avere una tomba, voglio che ci sia scritto prima di tutto il mio numero. Con una piccola operazione di chirurgia plastica potrei toglierlo, in qualunque momento. Ma credo che quel numero sia un monumento alla vergogna di chi l’ha impresso sulla pelle, e credo che sia anche un motivo di onore per chi, avendo perso tutto nella Shoah, non ha perso la sua mente, non ha perso la sua anima, non ha perso la memoria di quella serie interminabile di numeri. (Parte 4) | I wear my number proudly: the number 75190. In this the Nazis succeeded brilliantly: those of us who came home to tell our story have in effect remained the number we got in Auschwitz. They wanted to replace millions of men and women with numbers, and once they were dead, they would not be human beings, but numbers, and nothing can be said about them. And those of us who returned have in effect remained that number. I tell my children all the time: I want my number put on my tombstone before any other words. I could remove the number at any time with a bit of plastic surgery. But I believe that number is a monument to the ignominy of those who placed it on my skin; and I believe it is also a tribute to those who, having lost everything in the Shoah, did not lose their mind, did not lose their soul, and did not lose the memory of what that interminable string of numbers means. (Part 4) |

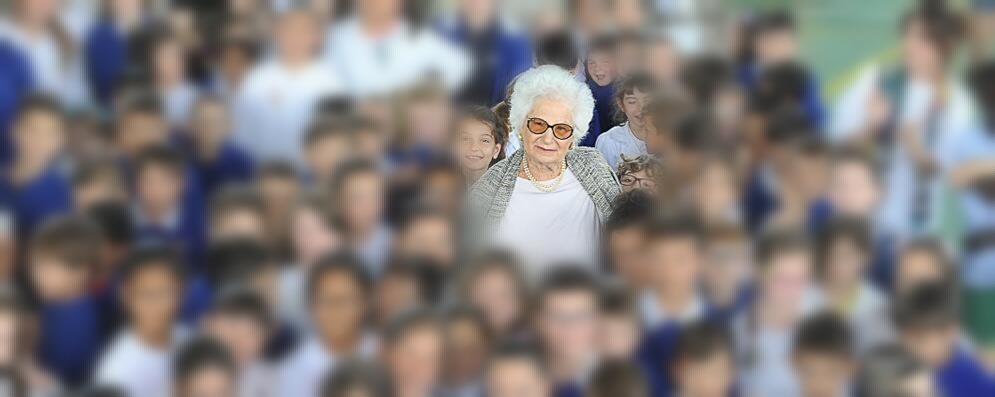

| Quando vado a parlare nelle scuole, nelle università, nei circoli, nelle parrocchie, ovunque mi invitino, vorrei prendere per mano quelli che mi ascoltano, visto che la mia testimonianza non è né un’elaborazione né uno studio teologico, critico, filosofico, storico, psicanalitico, ma una storia personale. Vorrei prendere per mano le persone e invitarle, mentre racconto, a non perdere nella vita nessun momento di amore verso coloro che ci vogliono bene… Sono momenti preziosi, che caricano per tutta la vita. | When I talk in schools, in universities, in centres, in churches, or wherever else they invite me to go, I would like to take the people who are listening by the hand because my memories are neither an elaboration, nor a theological, critical, philosophical, historical or psychoanalytical study, but they are my own personal story. I would like to take people by the hand and invite them, as I tell my story, to not lose a single moment of love in life, a single moment of love for those who love us…They are precious moments, moments which drive us forward our entire lives. Translation ©Matilda Colarossi paralleltexts.blog 2024 |

The complete story of Senator Liliana Segre, in 6 parts, can be found here on this blog at https://paralleltexts.blog/2020/01/26/liliana-segre-in-auschwitz-at-thirteen-lestweforget/

I would like to thank Liliana for responding to my email so many years ago, for letting me translate, for giving me permission to post it on my blog. M.C.

This work is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0