Here we are now in the realm of “nonsense” (like life today?) with a rhyme by Toti Scialoia. I suspect the jackals must be playing with “human” pieces on this chessboard today. Who is the stupid one, who the sceptical one, and why have we let them get so far in this horrific game of chess?

| from AMATO TOPINO CARO (1961-1969) TOTI SCIALOJA Due sciacalli giocavano a scacchi erano magri come due stecchi uno era scettico l’altro era sciocco uno pensava: “Se attacchi, mi arrocco?” l’altro pensava: “Se arrocco, mi attacchi?” e si scrutavano di sottecchi. | from AMATO TOPINO CARO [Dear sweet mouse] TOTI SCIALOJA A couple of jackals were playing chess both were as wiry as blades of grass one was suspicious the other senseless one mused: “If you attack, will I castle?” the other mused: “If I castle, will you attack?” and they looked at each other askance. Translation ©Matilda Colarossi 2025 |

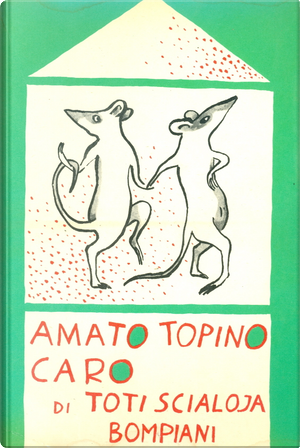

Toti Scialoja (1918-1998) was born in Rome. After a brief period in which he studied law in university, in 1937 he began to dedicate his time fully to painting. He took part in the resistance, and after the war continued to paint, collaborate with different art magazines, design sets and costumes for the theatre both in Italy and the United States. He took up writing poetry in 1961. Legend has it that “Toti was walking along the street with his eyes to the ground. In his head, he hears a sound, the ‘zzzz’ of a zanzara (mosquito). He immediately ‘sees’ the word (not the mosquito) and starts to take it apart: inside the zanzara is Zara, but also the beginning of Zanzibar. And inside Zanzibar? Is there not a bar?” (Paolo Mauri, from Versi del senso perso, Einaudi). His poetry is original, based on the tradition of nonsense poetry and the limerick; he published numerous works, many of which he illustrated himself. These include Amato topino caro (Bompiani, 1971), Una vespa! che spavento (Einaudi, 1975), Ghiro ghiro tonto (Stampatori, 1979).

As always just a note on the translation of rhyme: if in translation we must sometimes move away from the original to recreate the original, in rhyme the distance must necessarily grow. The choice of one word in a rhyme will dictate the other word choices. If I end my first verse with the word chess, that will inevitably influence my other choices (Scialoja uses the hard C and six S sounds: scaCChi, steCChi, scettiCo sciocco, aroCCo, attaCChi, sotteCChi. I chose the letter S and three hard C sounds: chess, grass, suspicious, senseless, castle, attack, askance). Other choices include adding or removing words that do not change the text but help the metre (due, two, is one)

Had I chosen to end the first verse in another word, jackal, for example (“A game of chess between a couple of jackals”, perhaps) then my choices would have all had to rhyme with L. I might, therefore, have chosen sceptical and nonsensical and castle and…what? The last verse needs an adverb and most adverbs end in LY so…

And that’s how I spend my weekends playing with sounds, mixing and matching for one poem that is both playful and meaningful (to me, at least). Enjoy. – M.C.

You can find the book Amato topino caro (Bompiani 1971) here.

The complete collectionc Versi del senso perso (Einaudi 2009), which I used, can be found here.

https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/